Comments from Richard Besser, MD, on Modernizing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The following comments were submitted by Richard Besser, MD, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) President and CEO, in response to a request for information (RFI) from Senator Bill Cassidy, M.D., ranking member of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. The RFI requested comments regarding opportunities to continue to modernize the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) is working to develop a Culture of Health rooted in equity that provides every individual in the United States with a fair and just opportunity to thrive, no matter who they are, where they live, or how much money they have. For fifty-one years, we have worked with partners across the country to bolster the nation’s public health system, produce rigorous science to guide public health practice and policy, and address some of the nation’s most pressing public health challenges. Many of our staff and leaders have also served on the front lines of public health at the local, state, and federal levels. I worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for 13 years, including serving as the acting director of the agency in 2009. Dr. Julie Morita, RWJF’s executive vice president, is currently serving on the Advisory Committee to the Director of the CDC in a voluntary capacity and previously served on President Biden’s COVID-19 Task Force. Dr. Morita and I were also trained through the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service, which focuses on responding to disease outbreaks and other public health threats through field investigation and action.

For these reasons and more, we greatly appreciate the opportunity to respond to the request for information on ways to modernize the CDC. We are not expressing views on specific legislation but rather sharing our perspectives on public health improvement strategies more broadly. Guiding our comments is the notion that a vibrant, effective CDC is essential to our nation’s health and safety as leaders from both major parties have recognized for decades.

Why Public Health and the CDC Matter

As you know, our nation’s public health system comprises governmental public health agencies at the federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial levels along with other public and private entities such as hospitals, human services agencies, and community-based organizations—all working to protect and promote the health of our country. As a field, public health is distinct from healthcare in that it focuses on prevention; considers communities, not just individuals; and addresses social conditions, not simply biology. A healthy society requires both public health and healthcare approaches, but the role of public health is often overlooked. Notably, most of the improvements in health and longevity in the 20th century were due to public health efforts securing cleaner water, safer food, healthier mothers and babies, less tobacco use, and reduction or elimination of many serious infectious diseases.

CDC plays unique and critical roles in our nation’s public health system, including:

- Gathering and analyzing data from across the country on health factors and health conditions;

- Developing science-based guidelines to shape public health practice and policy;

- Supporting state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies with funding, scientific guidance, and technical assistance;

- Educating the public regarding public health issues of common concern; and

- Serving as a leading voice in the federal government for public health.

Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health professionals across the country, including those at the CDC, worked tirelessly and heroically to reduce suffering and save lives, including more than 3 million through vaccination alone. However, the pandemic also revealed critical weaknesses in our domestic and global public health systems, stemming from historical and ongoing disinvestment in public health infrastructure as well as poor coordination among, and strategic miscalculations by, public health agencies. These manifested in testing delays, inconsistent and untimely communications to the public, and inadequate strategies to prevent racial/ethnic and rural/geographic disparities in COVID-related health outcomes. Furthermore, several important truths were confirmed—one, that opportunities for health in the U.S. are not equal; two, that what affects one person or community affects us all; and three, that holistic reforms across the public health system are needed.

With the help of outside experts, CDC critically examined its own performance during the COVID-19 response and proposed key reforms through the Moving Forward report. This effort was undeniably necessary, and, in many ways, it was unprecedented in terms of transparency and accountability. The report offers specific, thorough, and actionable recommendations addressing timeliness, clarity, and effectiveness in agency actions and related issues of governance, structure, and workforce. Importantly, CDC has begun to act on many of these reforms. Below, we highlight ways to build on these effort.

Funding

CDC and our public health system as a whole need sufficient, stable, and flexible funding. Sufficient funding would enable needed investments in core data capacities and workforce at all levels of government. For example, since FY 2002, funding for Public Health Emergency Preparedness programs at CDC has been reduced by nearly half (adjusted for inflation). In addition, a recent de Beaumont Foundation analysis shows that state, local, tribal, and territorial health departments need an 80 percent increase in the size of their workforce to be able to provide comprehensive public health services to their communities.

Stable funding would eliminate the boom-bust cycle that the public health system experiences during and after public health emergencies and allow for long-term planning, continuity in staffing, and leadership development. Flexible funding would empower CDC and its state, local, tribal, and territorial partners to address persistent and emerging threats and reduce silos within public health agencies. Currently, most of CDC’s federal funding is categorical—allocated for specific diseases or population groups. In turn, funding for state, local, tribal, and territorial health departments follows the same pattern, creating administrative burdens for all parties.

Mission

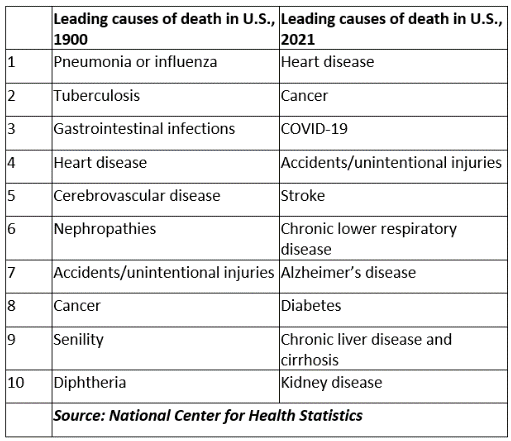

While CDC was established in 1946 to prevent malaria from spreading across the U.S., its mission expanded over time to address other major health threats faced by the nation, such as poor nutrition, tobacco use, and birth defects. During this period, the country was undergoing an epidemiologic transition with chronic diseases—like heart disease, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—overtaking infectious diseases as the leading causes of death. This transition has continued as is evident in the table to the right comparing leading causes of death in the U.S. in 1900 and 2021. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, heart disease remained the nation’s leading cause of death.

CDC’s mission must remain broad to address the preventable conditions that burden so many Americans while also building preparedness for the next public health emergency, which could be an infectious disease, a man-made biological or chemical attack, or a multi-faceted threat triggered by severe weather events like hurricanes, wildfires, or floods. Moreover, chronic conditions and infectious diseases are often interrelated at the individual and population levels and require a coordinated response.

In addition to these reasons to maintain a broad CDC mission, it is important to note that social, economic, and environmental factors account for approximately half of the observed variation in health across communities. These include the quality of education, affordability of housing, and safety of neighborhoods. These factors have even greater influence on the health of rural residents, disabled people, and African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and Asian Americans. While CDC is not the lead federal agency on these social and economic issues, it must continue to help public health system partners understand the connections to health and develop responsive programming. Ultimately, an equity-centered public health system—one equipped to support the best health outcomes for even the most socially disadvantaged populations—will best serve all of America. This is exemplified by the curb cut effect. Curb cuts in sidewalks not only made it safer and easier for people with disabilities to navigate their communities but also for parents pushing strollers, children learning to walk, workers transporting equipment, and older people getting exercise. In the realm of food systems, improvements to the nutritional quality of foods available through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) create better options for families across the income spectrum. RWJF shared detailed considerations on how CDC can foster equal opportunities for health in December 2022.

Structure and Governance

We applaud the structural changes proposed under Moving Forward, including a new cross-disciplinary executive committee to advise the CDC director; elevating science, policy, communications, and equity as cross-cutting functions; and re-establishing an agency-wide performance-management system. These shifts and others will help to break down silos within CDC and enable it to coordinate more effectively with partners in government and the private sector.

Conversely, new limitations on CDC functions would hamper the ability of the agency to respond to emerging issues and the varied, interconnected health threats faced by communities across the country. Underlying all these shifts should be a steadfast commitment by people within and outside of CDC, including Congress and the administration, to bolster CDC’s independence and protect it from political interference. This includes attempts to suppress or adulterate scientific findings and guidance and to undermine the credibility of public health officials. Admittedly, public health decision-making is never solely based on science because it requires considerations of interrelated social and economic outcomes, notions of the public good, and individual liberties. Even with these complexities, CDC should be able to analyze data, make policy decisions, and communicate guidance to the public directly with measured oversight and without politics exerting undue influence.

CDC must also pair strong national leadership with a decentralized model of action that empowers state, local, tribal, territorial, and private sector partners. More specifically, CDC should consider three important shifts: 1. Make public health funding available and accessible to a wide array of community-based organizations (CBOs)—such as social service organizations, community health centers, and voluntary organizations—by funding national intermediaries; 2. Support state, local, tribal, and territorial health departments with funding and technical assistance to build trust-based relationships with these CBOs; and 3. Network these governmental and community leaders, organizations, and coalitions into a national community health infrastructure. This infrastructure could serve both for sentinel surveillance (i.e., identifying failures and innovations in the system as early as possible) and action (i.e., working with governmental public health leaders to shape and implement solutions). As part of its COVID response, CDC supported incredibly important community-government partnerships related to rural communities, racial-ethnic minority communities, and community health workers, all of which could serve as the foundation for a national community health infrastructure.

Data and Communications

We commend the reforms related to data and communications under Moving Forward, including releasing scientific findings more quickly and in a comprehensible manner, establishing early and regular feedback loops with key constituencies to review implementation guidance, and focusing on communication efforts to the general public first with additional communications tailored to key audiences.

As noted under the above section of the letter on funding, an integrated national public health data system requires sufficient, sustainable investment. Additionally, as recommended by the National Commission to Transform Public Health Data Systems, CDC and other federal health agencies should develop and promulgate minimum standards for data collection, disaggregation, presentation, access, and interoperability in federally funded initiatives. These federal standards must be paired with a decentralized data strategy that resources state, local, tribal, and territorial partners and prioritizes territorialhyper-local, integrated data. As such, CDC should better understand and help to meet the diversity of needs among state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies (as has begun under its ambitious Data Modernization Initiative). For those with underdeveloped data capacities, CDC should make available data-savvy staff for local assignments and facilitate collaborations with regional universities. The latter model has been leveraged effectively by other federal agencies, like USDA. Rural communities will gain much needed support in understanding their health assets and challenges through CDC’s new Office of Rural Health. The office is poised to leverage data from CDC PLACES—a partnership of the CDC, CDC Foundation, and RWJF—which provides data on 27 health measures for every county, census tract, ZIP code tabulation area, and Census Designated Place with a population of 50 or more in the country.

In terms of communications, CDC should conduct audience analyses—involving the public as well as state, local, tribal, and territorial health leaders—to understand their knowledge, needs, and priorities. Messages developed based on these analyses would be best communicated by trusted messengers. Here, again, the national community health infrastructure described above would be critical, allowing not just dissemination of information from public health experts to the public but two-way dialogue that values the expertise of all. CDC itself can invest in leaders and staff who represent the nation’s geographic and cultural diversity and who can draw on lived experiences when listening to partners and designing and deploying communications strategies.

Role of the CDC Foundation

The CDC Foundation fills several critical roles in support of the CDC and the public health system as a whole, including: 1. raising private sector funds to augment (but not displace) public investments; 2. convening public and private sector partners to address complex public health challenges; and 3. facilitating shared learning among state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies.

RWJF has a longstanding partnership and funding relationship with the CDC Foundation, especially as it relates to facilitating a rapid federal response to public health emergencies, like COVID-19, Ebola, Zika, and mpox (monkeypox), given the lack of discretionary funding available to CDC for this type of rapid response. In addition, Dr. James Marks, a former senior RWJF leader, serves on the CDC Foundation Board along with Dr. Robert Litterman and Dr. Jeffrey Koplan, current and former members, respectively, of RWJF’s Board of Trustees. Dr. Leah Devlin, a member of the RWJF Board of Trustees, will conclude her time as a CDC Foundation Board member this week. During my years at CDC, I worked closely with the CDC Foundation.

With COVID-19, RWJF funding to the CDC Foundation helped to support various efforts, including reducing transmission and illness in the South (with an additional focus on rural communities) and engaging businesses as partners in COVID response and workplace reopening. With regard to convening public and private sector leaders and organizations, the CDC Foundation has helped to spur progress on key strategies, such as public health data modernization and charting a future for public health in the U.S. As part of data modernization, RWJF has supported several high-impact data projects with the CDC Foundation and the CDC, including CDC PLACES as noted previously. Finally, in terms of facilitating shared learning among state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies, the CDC Foundation has supported initiatives dedicated to collaborating effectively with other governmental agencies, leveraging community advisory boards to build trust in public health, and making use of data to facilitate community partnerships.

About the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) is committed to improving health and health equity in the United States. In partnership with others, we are working to develop a Culture of Health rooted in equity that provides every individual with a fair and just opportunity to thrive, no matter who they are, where they live, or how much money they have.

Related Content

Public and Community Health

Expanding our thinking about community partnerships that work together to pursue public and community health.

1-min read

Adapting to Shifts in Policy

Comments on proposed regulations and related documents published by U.S. federal government agencies.

Ways to Support and Strengthen the CDC

Comments submitted by Richard Besser, MD, on ways to reform and improve upon the CDC.